Essays & Reviews

“Jack Boul lingers in the memory like the fragment of a melody.“

PAUL RICHARD, Washington Post, 1988

- Essay by Eric Denker, The Concoran Gallery of Art

- Essay by Ben Summerford, Professor, Art Department – American University

- Essay by Jack Boul

- Review by Paul Richard, Washington Post Art Critic

Intimate Impressions: Monotypes and Paintings by Jack Boul

Essay by Eric Denker The Corcoran Gallery of Art

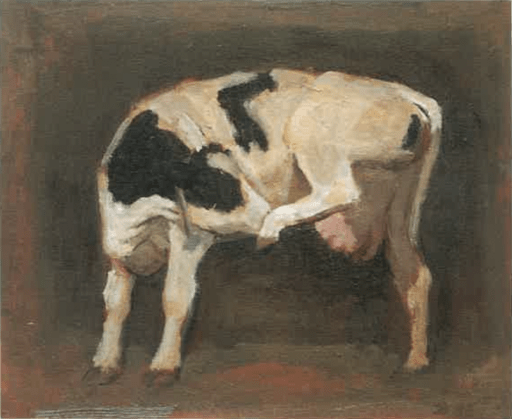

Jack Boul’s art combines exceptional technical skill with a deeply poetic sensibility. His small-scale monotypes and paintings economically capture the timeless elements of the visible world. He is fascinated by landscape, from the rolling pastures of Maryland to the deserted beaches of North Carolina. Yet, the artist is as apt to be attracted to the gritty, city imagery of Baltimore and Chicago as he is to the bucolic countryside. He depicts such familiar urban sights as water tanks and train yards with the same acuity as he gives to the charm of a Parisian cafe or a Venetian canal. He is devoted to the beauty of the C & O Canal, and has a singular fondness for the shapes of cows. Boul’s artistic interests extend from barnyards to barbershops, from wheelbarrows to watering cans. In each image, his spare, simple constructions attempt to convey the essential, characteristic elements of his motif.

Many of the artist’s finest works center on the human figure and its myriad expressive possibilities. Occasionally he represents a model standing in the studio, while at other times he might select a solitary figure passing the time on a park bench. Often Boul portrays groups of people, in a restaurant, in the loge of a theater, or simply seated around a table. These encounters take many forms, at times in a workplace, sometimes in public, or in an intimate space, but they always exhibit the artist’s profound understanding of human relationships.

Boul is drawn to the inherent poetry of still life, with a particular affection for the simplicity of an individual form, an isolated vase, or the shape of a loaf of bread. As with other subjects in both monotype and painting, he returns to these objects repeatedly to explore the forms from different angles and in different poses. Boul also has a fondness for animals and birds, both domestic and in the wild, explored individually or in characteristic arrangements.

The intimate scale of the artist’s works belies their monumental form and balance. Boul’s subjects vary, but the content is always tempered by an appreciation of the compositional structure that informs the finest old master painting. While Boul prefers to work in the presence of his motif, or from drawings, he carefully avoids extraneous details: his monotypes and paintings seek the essence of their subjects, reducing the details of everyday surroundings to characteristic forms and gestures. As a teacher, Boul often quoted Delacroix dictum, “I only began to do something of value after I had forgotten enough small details to recall the really poetic and striking aspects. Until then I was plagued by an infatuation for accuracy which most people mistakenly identify for truth.” Boul’s work transcends the actual appearance of his subject to obtain a more universal relevance. Although his art has remained steadfastly representational, he has always maintained that all art is essentially abstract, as much about relationships as about the ostensible subject matter. Boul is concerned with the relationships of light and dark areas, of the contrast of sharp to soft edges, of the balance between depth and surface, and of the geometry of the composition. These issues are at the core of his artistic achievement, a body of work whose content reflects the artist’s ongoing engagement with his environment tempered by the search for more universal artistic truths.

Biography

Jack Boul was born in Brooklyn in 1927, and grew up in the South Bronx, the son of a Russian emigre father and a Romanian mother. He attended the American Artist’s School in New York, before being drafted into the United States Army. He served in an Engineers battalion as part of the US occupational forces in and around Pisa, Italy. After the war, he moved to Seattle, Washington where he studied on the GI Bill at the Cornish School of Art, graduating in 1951. Later that year he moved to the Washington metropolitan area to continue his studies at American University. He exhibited in the Annual Area Exhibition at The Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1951, and again in 1954, 1956, and 1958. Boul also appeared in a number of group shows at the Baltimore Museum of Art in the 1950s. In 1956 he appeared in the Sixty-Fourth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Washington Artists, in a show juried and dominated by abstract expressionists. In a generally negative review, Florence Berryman of the Washington Star wrote, “The real puzzle picture in this show is Jack Boul’s dainty naturalistic miniature Olney Landscape, somewhat primitive in effect, which seems as out of place here as a bon bon at a barbeque.”

In 1957 Jack Boul received his first solo showing, at the Franz Bader Gallery, attracting positive reviews that cited him as a promising young artist. In 1960 he had a one-man show at the Watkins Gallery at American University, where later he began to teach in 1969. During his fifteen years as a professor of art at American University, Boul showed regularly at the Watkins Gallery. He had his first museum exhibition in 1974 at the Baltimore Museum of Art in a three-person exhibition that garnered several positive notices.

In 1984, after fifteen years teaching at American University, Boul became one of the first faculty members of the new Washington Studio School. During ten years of teaching painting, drawing, and monotype, he had annual one-man shows in the Courtyard Gallery of the Studio School where he continues regularly to show today. In 1986 Jack Boul was part of a two-person exhibition that included the work of the late Washington artist Peter DeAnna, organized by the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, and later shown at the University of Maryland in College Park. In addition he contributed to numerous area group exhibitions, most prominently with eight oil paintings in the traveling show Still Working: Under Known Artists of Age in America shown locally at The Corcoran Gallery of Art. He retired from the Studio School in 1994 to devote his time to printmaking and painting.

Boul as Teacher: “There’s Just One Little Thing… “

Jack Boul has been teaching in the Washington area since the 1950s. His students from Smithsonian classes, American University, and the Washington Studio School describe Jack as a soft spoken but firm instructor, mixing words of praise for specific areas of a student work in progress with insightful commentary on areas of weakness. He often started tactfully by praising a particular passage, before beginning, “there’s just one little thing…” He skillfully leavened his criticism with encouragement and with his self-effacing, dry sense of humor. Jack is known for his integrity and candor both as an artist and as a human being. He never shrinks from offering honest criticism, whether of a student’s work or of the paintings of contemporaries, or even acknowledged old masters. He laced his instruction with examples of old masters, with a great affection for Rembrandt, Velasquez, Corot, Sargent, Whistler, Vuillard, and Eakins among many others. Once, while in Venice with a student, he was taken to view a painting the pupil greatly admired, a late Pieta by Titian. Jack proceeded to critique Titian for a lack of balance in the use of light and shadow.

Boul’s teaching philosophy always began by emphasizing the larger elements of composition. He often paraphrased the French nineteenth-century painter Camille Corot, instructing students to not be in a hurry to get to details, but first and foremost to be interested in the masses and the larger character of the picture. Sometimes Boul would project slides of famous works deliberately out of focus so the students would begin not by recognizing the image but by seeing the larger areas of light and shadow. He stressed the inner geometry of the picture, the shapes and divisions within the compositional structure, and the relationship of the component parts of a painting. Students also remark on his repeated reference to Delacroix’s ideas about composition, that the French painter admitted that he only began to do something of value when he had sufficiently forgotten the small details so as to recall only the most striking, poetic aspects of the motif. Despite emphasizing the importance of structure, Boul always has denied the possibility of a formula that could be employed as a short cut to composition. Each artistic decision is formulated on the demands of the particular arrangement and the sensibility of the artist. Boul’s teaching principles reveal his approach to the underlying structure of his monotypes and paintings.

Monotype

Jack Boul was involved in printmaking throughout the early part of his career, but he only began to experiment with monotype in the early 1970s. In the monotype process, an artist creates an image by painting with viscous ink on the surface of an unworked plate. The ink on the plate can be worked and reworked until the artist is satisfied with the design, and then printed by hand or with an intaglio press. The image is called a monotype, since only one vivid impression can be made from the design on the plate. Monotype is the most direct and painterly of all print processes, paralleling the technique and resulting appearance of an oil. The fluid surface can be manipulated for a variety of different effects, but is particularly adept at suggesting dark interiors and night time illumination. Though the monotype process is at odds with the traditional function of printmaking, which is to make multiple originals, it has become one of the most popular forms of printing today.

The Genoese artist Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione pioneered the use of monotype in the mid-seventeenth century, but only in the late nineteenth century did the process blossom into a widely accepted form of printmaking. Degas was the greatest proponent of monotype, learning the process from Comte Ludovic-Napoleon Lepic, an obscure printmaker of the era. The French artists Pissarro, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec all experimented with the medium, as did Picasso, but in the twentieth century Americans have had the greatest interest in the expressive potential of monotype. Maurice Prendergast, John Sloan, and Robert Henri utilized monotype in the early years of the century, while Milton Avery, Mark Tobey, Richard Diebenkorn, Michael Mazur, and Wayne Thiebaud have exploited the potential of the medium in contemporary art.

Jack Boul has always maintained that monotype is the easiest technique to learn, simply involving painting or drawing on a blank surface, and then printing. Though the technique is easily acquired, the mastery of the process requires discipline and perseverance. Boul began with the most basic approach, but developed an array of sophisticated variations that he employs for subtle effects. In many cases Boul executes an image in a brief period, retaining a sense of the immediacy of creation. He may be pleased with one part of a print, but feel that other sections are less successful. Boul sometimes keeps an impression because there is some aspect of it that interests him, but he is a perfectionist who only regards approximately one out of twenty images as a completed work. At times he gains the desired result on the first pass through the press, but most often he reworks the remaining ink on the plate with additional ink and brushwork.

By diluting the ink with turpentine, Boul can produce an infinite range of gray values from the black ink. The gradation of values in a monotype often suggests color. Although occasionally Boul has produced color prints, he prefers a black etching ink for his monotypes. The artist can effect the thickness of the ink, and the painterly qualities of the edges and lines by varying the pressure of the press and the number of felts that are used in printing. Sometimes Boul begins a design on a blank plate, at other times he may cover the surface with ink and create an image by wiping white areas out from the dark background. He may use his fingers, or large brushes, or cotton swabs to create an image, depending on whether a particular subject requires crisp outlines or soft contours.

Boul approaches monotype with the same principles as he does painting. No distinction exists in the artist’s mind between the acts of painting and printmaking. Many times Boul treats the same subject in both, creating images in color and in black and white. The inspiration for an oil may precede a monotype or vice-versa, with no set pattern. A monotype may be a mirror image of a painting, or it may have a parallel orientation. In both media he remains interested in the larger compositional relationships, areas of dark and light, of form and of space, and of the division of the surface into its basic geometry. He often has made reference to the ideas of the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, who said that while the material contains utility, the immaterial contains essence. The artist has an ongoing interest in the relationship of masses and voids in his compositions.

Boul repeatedly returns to favorite motifs, often over a long period of time, to explore the expressive possibilities of a theme. The artist never intended these works to be exhibited serially, but seeing a group of images inspired by the same motif reveals the variety of solutions offered by different techniques and approaches. Boul’s many images of the C & O Canal, for example, were produced over a thirty-year period, and show immense variation in size, shape, color, cropping, and focus (plates 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11).

While Boul acknowledges the inspiration of a particular subject, he resists the identification of his pictures with specific motifs. He prefers generic rather than informative titles. Figures are rarely named, landscapes and cities are unidentified. He prefers his work to evoke the universal rather than to define the particular. Boul is in agreement with an artist he admires, James McNeill Whistler, who said that nature rarely produces the harmony worthy of a great picture, but that the artist must pick and choose and group the arrangement necessary for a work of art.

While stressing the essentially abstract nature of painting, Boul has remained steadfastly representational in his approach to the subjects of his monotypes and paintings. Occasionally his work pushes the limits of representation, in the spare Abstract Landscape (plate 12) for example. With rare exception, he is intent on depicting familiar aspects of the world around him.

The Subjects of the Artist

Boul has a strong predilection for landscape. His pictures capture a broad range of motifs varied by specific seasonal conditions. We see the C and O Canal in spring or in autumn, in brilliant sunlight or under cool, gray, overcast skies (plate 10). The artist subtly describes a steamy summer afternoon in the rolling hills and valleys of Frederick County, or the almost imperceptible morning haze that hangs over a Tuscan countryside. His paintings has often been compared to the work of Camille Corot, or the Barbizon School, artists he esteems, but the resemblance is more in the subject matter than in the handling. Boul’s application of paint and tonal harmonies are more closely related to the approach of Silvestro Lega, Giuseppe Abbati, and Giovanni Fattori, members of the Italian Macchiaioli group that the artist has long admired. Boul is an avid student of art history, but though his work resonates with the knowledge of the past, his images remain resolutely contemporary, transcending any connections to the old masters. Landscapes such as Hoeing (plate 29), Queen Anne’s Lace (plate 45), and A Corner in the Country (plate 27) are American images of our time.

A number of Boul’s most innovative landscapes are the result of a radical simplification of the pictorial means. The monotypes Abstract Landscape and C & O Canal (plates 12 and 6) utilize a few suggestive brush strokes to convey the artist’s perception of nature. Boul has always venerated the economy of Rembrandt’s landscape drawings, and he reflects an affinity for the Dutch master’s spare style. Similarly, Boul’s diminutive images of beaches reduce the composition to a few essential horizontal bands only interrupted by clouds above, or by rocks in the surf below (plate 34). These minimalist compositions are strongly reminiscent of the economy of Whistler’s seascape sketches. On occasion, Boul all but abandons the landscape to concentrate on the sky and formations of clouds (plate 50).

Jack Boul grew up in the 1930s in the inner city, and he has always retained an affection for urban forms. He depicts cityscapes with the same approach he uses in landscape, looking for a solid geometric underpinning for the formal elements of his design. Views across rooftops provide Boul with a series of forms and shapes that appeal to his artistic sensibility (plate 139). He renders unromantic urban motifs such as railway yards (plate 38), trestles, and water tanks (plate 18) with the sympathetic eye of the city dweller. Chicago Underpass (plate 30) is a characteristic example, exploiting the basic geometry of the architecture as the foundation of the pictorial contrast of mass and space. The artist emphasizes the essential flatness of the design by allowing the grain and warm tone of the under panel to subtly merge into the foreground. The tension between surface and depth, and the integration of open spaces and strong architectural elements is a hallmark of some of Boul’s finest works. In Venetian Alley (plate 25), the artist balances the sun-lit bricks and stucco of the wall with the shadows and depth of the passageway. In the related monotype, Sottoportico (plate 21) the pictorial elements are even more radically simplified, the entire right side of the composition barely suggested by a light gray wash of ink.

Similarly, Boul’s interiors are arrangements in light and dark masses dictated by the geometry of windows, mirrors, frames and furniture. In the early Hyattsville Studio (plate 60) the artist balances the rectangles of the windows and the reflections on the floor with the geometry of the desk and easel. Boul used a similar tact in the evocative monotype Venetian Light (plate 32) with its strong morning sun penetrating the shadows of the Gothic palace through the Moorish fifteenth-century windows. The glare of light is contrasted to the firm structure of the windows and walls. Museum Guard (cover and figure 1), a tonal masterpiece, is a meditation on the use of framing devices. The painting contains a marvelous play of rectangular shapes, the form of the central door mimicking the shape of the canvas, and playing off against the walls, the wainscoting, the picture frames, and the truncated doorjamb in the background. The lines of the pediment and the gently curved profile of the seated guard discretely soften the severe angularity of the design. Boul tackles a more challenging space in Paris Cafe (plate 75) the mirrors containing a series of complex reflections of the interior space. The artist is fascinated by the spatial arrangement of restaurants and cafes, returning to the theme often throughout his career. Boul’s many images of Haussner’s Restaurant in Baltimore (plates 74, 76, 79, 97) are explorations of the linear structure of the wall decoration used as a foil for the oval shapes of tables and for the couples seated in the foreground. Small human figures inhabit many of the interiors, an integral element in the overall design. In Reading (plate 84) the seated woman in the rocking chair is an essential part of the design, absorbed into the tonal harmony in a fashion evocative of the flat, decorative effects in a painting by Vuillard.

Many of Boul’s works focus on the figure as a major element. Sometimes he depicts simply a head, or a bust length figure, isolated from the surrounding environment. Many of his figures are lost in thought, captured in characteristic poses of age or fatigue (plate 65). Boul’s figures inhabit museums (plate 69), or solitary cafes (plate 81), or elaborately decorated, domestic interiors (plate 96). Sometimes they sew, or weave, or garden (plate94), but they rarely move. Tango (plate 134) is a rarity in Boul’s oeuvre, a rhythmic design of a couple frozen in the midst of the dance. The related sculpture (plate 127) is also exceptional in its depiction of movement.

The artist has always been attracted to people engaged in everyday public and personal activities. The Entertainer (plate 93) depicts a performance on the stage of an old music hall. The Barbershop (plate 141) is a quotation of familiar, quotidian business. Boul’s images also can be intimate, charged with emotional overtones, as in The Proposition (plate 52), or The Edge of the Bed (plate 54). The soft focus and suggestive quality of the monotype process is especially well suited for provocative imagery.

The human figure is prominent in one of the most unusual of all of Boul’s works, his series devoted to the holocaust. Boul, who served in the European theater just after the war, knew of Nazi atrocities from the accounts of other servicemen. He wrote:

“In 1946 I was a sergeant with the U.S. Army Engineers Corps stationed at a prisoner of war camp outside Pisa, Italy. I remember showing German prisoners of war pictures of the liberated concentration camps. They refused to believe the pictures. ‘You have your propaganda and we have ours.’

I saw the movie Shoah in 1987 and was very moved. It showed the cattle cars that transported people to the concentration camps, the furnaces where people were cremated, and the fields where the ashes were scattered. It never showed the victims. I remembered the photographs I had seen in Italy forty years earlier, and decided to look for other photos of the camps.

In the United States Archives I found hundreds of photographs from many different concentration camps. I looked at the photos for days, and made drawings. In my studio, I made these monotypes from the drawings. I wanted to make something that would help to keep that memory alive.”

While the subject of the set is the nightmare of the holocaust, the more universal content examines man’s inhumanity to man. As with Callot’s Miseries and Misfortunes of War from 1633, and Goya’s Disasters of War from 1810-14, Boul’s moving images transcend the specific circumstances to become a commentary on human suffering.

Cows are a great favorite of the artist. The artist regularly drives out to the countryside in search of cows to render. Boul is attracted to their shapes and silhouettes, individually (plate 102) as well as in groups (plate 115), the way they stand (plate 114) and the way they lie down (plate 145). In landscapes, he is interested in the way cows help to tie a composition together, either as a solid mass or to establish depth. He depicts them in infinite combinations, often overlapping and blending individual creatures together to make interesting and unusual forms (plate 112). As he has often said to students “cows do a lot more than stand out there and just eat and moo.” Cows have become a signature subject with Boul, who depicts them standing in pastures (plate 116) and in paddocks (plate 40), involved in all types of characteristic bovine behavior–scratching, eating, sleeping, and drinking (plates 111 and 152).

Boul also is attracted to the shapes of birds. He depicts them singly (plate 137) and in clusters on feeders (plate 107). He renders them flocked together on electrical wires, becoming the aviary equivalent of a musical score (plate 91). The purity and directness of these depictions are reminiscent of Wallace Steven’s poem, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Boul also portrays individual dead birds (plates 95, 105 and 106), part of a long tradition that extends from Baroque game pieces to Albert Pinkham Ryder’s oil at The Phillips Collection. Theses small yet poignant images refer inevitably to a meditation on death. Similarly, Boul’s image of Kosher Butcher (plate 104) can be read as both a reference to a familiar motif from the artist’s past, and as symbolic of mortality.

Boul’s other signature subject is the wheelbarrow. The simple shape and sleek lines of this common garden implement provide Boul with a motif of great purity (figure 2). Writing in the Washington Post in 1988, Paul Richards described his reaction to this image.

“‘Wheelbarrow’ by Jack Boul lingers in the memory like the fragment of a melody. It’s scale is domestic (it’s not much bigger than a postcard). Its theme is unheroic. That lovely little monotype–its half painting and half print–could hardly be more modest, yet I’ve thought of it all day. Its colors are subdued. They are only blacks and grays, and yet they mange to imply the quiet buzzing of midsummer, the glare of midday sunshine, the warm weight of the air and the deep green of the grass.”

The simplicity of the image is based on Boul’s exacting distillation of the essential nature of the wheelbarrow, its volume and its shape. Nothing is inherently picturesque in this homely vehicle, yet Boul endows it with a timelessness and monumentality beyond the scope of its humble function. The wheelbarrow is an ideal metaphor for Jack Boul’s achievement. He continues to produce monotypes and paintings and to actively exhibit his work. He has tirelessly pursued the perfection of his art over a period of more than a half a century. He is a model of artistic integrity and industry, whose exhibition at The Corcoran Gallery of Art has been well earned and is richly deserved.

- Essay by Eric Denker, The Concoran Gallery of Art

- Essay by Ben Summerford, Professor, Art Department – American University

- Essay by Jack Boul

- Review by Paul Richard, Washington Post Art Critic

Essay by Ben Summerford

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TRUE ART AND FALSE ART may lie in the intentionality of the act. To understand intentionality in art, one must see that it deals not simply with a mechanical aim followed through to conclusion, but rather with a proper series of connections among physical, intellectual and emotional impulses. When these connections are properly functioning they allow the artist’s attention and consequently his aim for the work of art to be directed to a higher level than is possible otherwise.

One knows examples of art in which technical proficiency is present but in which the intellectual and emotional qualities are not. In the same way, the emotional or intellectual properties of a work may be adequately developed, while other aspects are lacking. It can be observed that intentionality is not merely an idea in the mind of the artist, but may more properly be viewed as an act of discovery. Since it leaves its trace as a material fact in the work, it may perhaps be described as having a flavor of veracity. This flavor can occur only when the purpose has been pure and the purest purpose may be that which exists for the education of the artist himself. This altogether innocent purpose has the power, because it is real and not imaginary, to ennoble even small aims.

An artist is a receiving station for information which may act upon his psychical functions in such a manner that their manifestations may be heightened. He designs his habits of work in such a way that higher levels of consciousness may be encouraged to occur. This statement may seem obtuse, but it is, from one angle, as each true artist knows, quite a practical aim. It may exist in the simple fact of maintaining an attitude that each new work must be discovered through. the physical act’s being directed by pictorial intelligence and emotion. Such real intelligence and real emotion can be described as existing in art only when they are produced by and for the artistic problem. Works of art by the same artist can be viewed as serial only in the sense that each is the product of the rediscovery of veracity. It would seem true that the more such a search for veracity is pursued, the more it becomes the property of the artist. When the habit is that of truth, consciousness of the artistic act and its inner meaning is increased incrementally.

It has interested me that many artists draw or sketch all their lives without exhibiting these drawings. Beyond the period when drawing is a learning process, as in the education of a student, it is primarily a private event in the artist’s life. The reasons he continues to draw are numerous, but chief among them is this search for veracity. A drawing, because it is usually accomplished within a narrow time frame, is freed of the obtrusive breaks in attention that are endemic to painting. A fine drawing, often for that reason, may exhibit, to the highest degree, the inner workings of the artist’s sensibilities.

These monotypes of Jack Boul are drawings of the finest order and they call to mind other works such as the great series of monotypes of Degas and the drawings of Rembrandt. It is exalted company and one achieves it only through a sprit of intentionality and truth inherent in the work. Their beauty is, in some considerable degree, the product of a formidable spontaneity. Yet “spontaneity” is not an adequate word to describe the experience. Is not spontaneity a product of intentionality, as we speak of it? When we use that term as one of approbation, it would seem true that we connect it to veracity. It could be termed the condensation of the complex to a stage of simple, swift, and emotional understanding. All the clues, as they are reduced, must be more exact, in order that spontaneity not fall victim to a shallow bravura. These drawings by Jack Boul do not falter in their search for truth.

The publication of this book of monotypes is like a gift to art lovers. At a time when it is hard even to find an interest in art with such purpose as that of the art of Mr. Boul, it is important that these drawings may be seen by more than merely his friends. Such works do not need praise. They insist upon communication and by so doing discover their audience in high places.

Ben Summerford

Professor, Department of Art

American University

- Essay by Eric Denker, The Concoran Gallery of Art

- Essay by Ben Summerford, Professor, Art Department – American University

- Essay by Jack Boul

- Review by Paul Richard, Washington Post Art Critic

Essay by Jack Boul

Dear Joe,

I find the more I try to put my thoughts down about painting, the more they elude me. I am not a mystic, but to me there are so few absolutes in painting. Things are always in relation to each other.

I have always been interested in what information one takes from real life when painting.

The trees and windmills in Mondrian’s early paintings are a vital part of the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal divisions in his paintings. They are shapes, and locations first, and objects later.

Ryder found the abstract rhythms of nature in the large masses pushing and pulling against each other.

What makes a painting have meaning in its time and beyond? Corot painted “Melancholy” in the 1800’s and it is timeless.

I thought if I listed some of the painters who influenced me, it might tell me something. Rembrandt, Corot, Mondrian, Vuillard, Abbati, Sickert, Morandi, Ryder, D’Aristra, Kerkham, Kulicke: they all make marks on a flat surface. They are different and yet the same. Like a family.

I am interested in the first impression, the distant impression one gets looking at things with your eyes half open. The gesture of things, how they lean, or stand, or sit. I am interested in color before it becomes a rendered thing. How do you enter a painting, move around in its space, turn the corners?

I like thick paint, and thin paint

I like dry paint, and wet paint

I like hard edges, and soft edges

Sometimes I can put them all together

When I do I am happy for a little while.

- Essay by Eric Denker, The Concoran Gallery of Art

- Essay by Ben Summerford, Professor, Art Department – American University

- Essay by Jack Boul

- Review by Paul Richard, Washington Post Art Critic

A Small Brush With Nostalgia

Jack Boul’s Monotypes Delve Into The Past At Corcoran

By Paul Richard, Washington Post Staff Writer.

November 12, 2000.

You know those upright row houses of red Victorian brick that line this city’s streets?

Well, Jack Boul’s little pictures are just as Washingtonian, and just as kind and seldom thought of. There isn’t one of those old houses–with their sophisticated brickwork, their pointed, tiled caps and their pleasing air of yesteryear–that wouldn’t be improved by the hanging (in the hallway near the stair, or beside the reading chair) of his gentle works of art.

Boul’s been making them in Washington, learnedly and surely, for nearly 50 years, and you sense that when you see them. They have mood about them–a kindliness, a reticence, an acceptance of the past–that those who’ve lived here for a while will recognize at once. It’s hard to believe that this good Washington artist had never had a solo show in a Washington museum. But that has now been fixed.

Boul first showed at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1951 and is now, deservedly, showing there again. His Corcoran retrospective is called “Intimate Impressions: Monotypes and Paintings by Jack Boul.” One true part of the story of what has happened to painting in Washington in the past half-century is seen distinctly in his pictures, which are neither hot nor hip.

He doesn’t make wall-swallowers. Many of his monotypes are little, memory-retrieving objects no larger than a postcard. Boul produces them on an old-fashioned screw-down proof press in Northwest Washington, which means that he works small. He’s also swift. His hand is quick (you know that from the darting movements of his brush) and he also is quick at seeing. Boul is excellent at benign glimpses.

His subjects are as unthreatening as a stroll in the country or a visit to the Phillips. He sees an empty wheelbarrow bright in the back yard, glowing in the sunshine of a summer afternoon, and in a few strokes captures the essence of that vision. His monotype technique evokes Edgar Degas’. The modernists of Paris liked to walk through neighborhoods and record the quotidian. Boul sees a bald man in a barbershop getting a haircut, and, through a flurry of his dispersed markings, so do we. He sees a couple dining in Baltimore at Haussner’s, or his wife reading the newspaper in the living room, or cows. Nice bucolic cows. The man makes pleasant pictures.

And they are pictures with an unexpected kick. Boul’s retrospective at the Corcoran delivers to the brain bracing little jolts of a strong emotion sensed seldom in contemporary art. The emotion is nostalgia, and nostalgia isn’t chic.

Many living artists, here as elsewhere, scorn it. They shoot, instead, for the startling, and dream of showing in Manhattan, and wrap themselves in novelty, and make their objects big. Boul has gone another way.

He never went for the big bucks. He’s always preferred teaching to celebrity, and he has steadily studied. To make such prints as his requires connoisseurship. You look at Boul’s monotypes and you somehow know how many Rembrandt etchings, Hopper streetscapes, impressionist oils and Constable cloud studies he’s looked at, and not in reproduction either, but on museum walls.

The Boul show, seen in Washington, urges intricate remembering. Pause, it seems to say, retrieve and recollect.

Those familiar with Washington art history remember how Duncan Phillips–in order to promote here the quick, slightly blurry, domestically scaled, depictive painting he so loved–opened in his house a school to teach that sort of art.

And they remember how that school moved whole to American University, where members of the faculty (Ben Summerford, Sarah Baker, Robert Gates, Jack Boul) kept that brushy faith alive?

And how, in 1984, that sort of teaching moved from American to Georgetown, to the Washington Studio School, which Jack Boul helped to found?

What sets him apart from the mainstream tradition of painting in Washington is his color. Boul is not a colorist, except by implication. He uses one ink only (Weber’s Intense Black), but he thins it so successfully that in his many grays the viewer half-imagines the tones of yellow sunshine and the many greens of turning leaves when wind moves through the trees.

Boul’s monotypes are one-of-a- kinders. Because he makes them on a press, squeezing moistened paper against a copper plate, I guess you’d have to call them prints, but I can’t help it, I still think of them as paintings.

Etchers use acid to eat grooves in their copper plates. The sharp burins of engravers plow furrows in the metal. Boul is doing something entirely different. He uses a brush and Q-tips and fingertips and rags, and with these things he paints directly on the copper plate before him. Paper, being absorbent, and canvas, being woven, brake the brush’s movement, but printing plates are shiny, and painting on their smoothness is like painting on glass. Boul’s method is a fluid one. He gets to slide his ink around on a slippery surface before he pulls his print.

How much pressure is applied in the printing press matters a lot. Boul partially controls it by the way he wraps his paper-and-plate sandwiches in felt blankets. How much ink he wipes from his plates before printing is similarly crucial. In the working up of monotypes, moistnesses and pressures, blackest blacks and whitest whites and many intervening grays are kept in constant flux.

The technique, as curator Eric Denker reminds us in the catalogue, was pioneered in the 17th century by the Genoese Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, but was not accepted widely until the 19th century when Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Camille Pissarro and especially Degas began experimenting with its shiftiness. Some highly skilled American painters (John Sloan and Robert Henri, Richard Diebenkorn and Wayne Thiebaud) have worked in monotype as well.

It isn’t easy. To acquire full control of it takes much practice and much patience. Boul’s sense of speed is curious. Though his brushes move with speed, though he catches glimpses quickly, little in his art seems to happen in a hurry. It somehow slows you down to wander through his quietudes. Boul leads the mind through memory toward calmer days than these.

Under David Levy, its director, the Corcoran in recent years has been a bit uncertain. The museum is lively enough, but you never know what you’re going to see there–good art, bad art, Finnish cigarette cases, Annie Leibovitz’s magazine cover portraits, Ottoman carpets, or the pictures of Jack Boul.

That museum used to be where the artists of this city showed the rest of us their art. This show is right on target. Much credit for its appearing there should go to Eric Denker. Unlike most Washington curators, Denker, 47, holds a dual appointment. He is both a senior lecturer at the National Gallery of Art and the Corcoran’s curator of prints and drawings. He knows Washington. He knows its museums. He also knows enough about the history of the graphic arts to recognize Jack Boul as the best printmaker in town.

BOUL AT THE CORCORAN

“Intimate Impressions: Monotypes and Paintings by Jack Boul” includes more than 150 prints, paintings and small sculptures by that Washington artist.

Though Boul, who was born in Brooklyn in 1927, has been making art and teaching here for more than half a century, this is his first solo Washington museum show. Boul’s retrospective was organized by Eric Denker and is funded by the Nef Fund, a program supported by Evelyn Stefansson Nef to highlight the achievements of mature artists whose achievements merit “greater recognition and focused attention.”

The Corcoran, at 17th Street and New York Avenue NW, is open every day except Tuesday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and until 9 p.m. on Thursdays. For information call 202-639-1700. Admission is $ 5 for adults, $ 8 for families, $ 3 for seniors, and $ 1 for students. The Boul exhibit will remain on view through Jan. 29.

Copyright 2000 The Washington Post.